Trinie Dalton’s short fiction is darling and traumatic

by Lonely Christopher

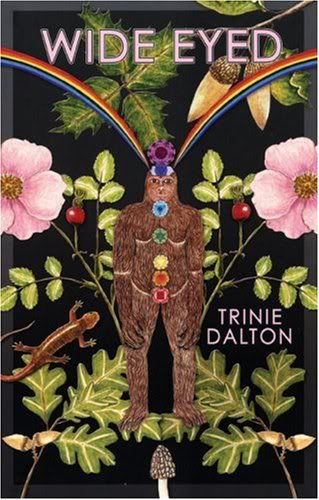

The cover art of Trinie Dalton’s book Wide Eyed, put out aught-five by Dennis Cooper’s Little House on the Bowery series from Akashic, features author-drawn illustrations of flowers, rainbows, unicorns, and a bigfoot type creature. I remembered the cover from seeing it at a bookstore a while ago; when I asked a friend about it he told me the cover was a good indication of the content and now I agree. What’s funny is that the collection is so magnificent. It has so many conceptual strikes against it, worst of all being creative writing, viz. fiction, published this decade. The persistence of kitsch (unicorns, for a start), the clever randomness (whimsical unpredictability!), and the ironic cultural references (the Flaming Lips, 80’s slasher flicks, Disney) are techniques shared with hipster fiction of the most abhorrent variety (unimportantly plaguing the aughts, hipster fiction is something we’re going to have to go back in a time machine to prevent). Dalton proves the same things that we’ve seen so abused by a whole youth culture can be used without guilt with delightfully winning results. She’s too mature to ruin the form like younger kids are and too clever to ruin the form like writers her age are. This is a compliment and a joy.

Anyway, if the stories were all sugar, narrated as they are by a very similar voice and personality that’s almost a sort of Amelie from a negative dimension, this writing would be impossible to stomach. What makes it work is how a Cooper-like disgust or anxiety spoons in a frilly bed with the ingenuous cuteness. This is a pretty fucked-up book --- plus it’s adorable. The Ben Marcus blurb on the back, which only praises aspects of innocence, love, and wonder, makes me suspect either Ben Marcus didn’t read Wide Eyed or else he’s a pretty disturbed person. These stories are ugly/pretty: a sinister violence becomes the undertow in a sparkling sun-kissed lazy river. The quality of this sentence is representative: “When I was in elementary school and first learned about the realities of rape, I remember riding home on the bus from a field trip to Disneyland and wishing I had been dragged into Adventureland, then raped behind Thunder Mountain.” No other contemporary work I can think of so vividly captures a world where everything being so not okay hurts but can’t murder being a happy person.

Nobody can do anything right and even when that fact is benign it’s still a lurking threat. The obsessions with unicorns, elves, woodland and sea creatures, botany, childhood, and candy only prove the darkness of these stories, which are about the awkward pleasures of aloneness, the façade of normalcy being punctured by humanity’s underlying ugliness, and the pathological failures of people to negotiate each other cleanly. Try writing a story in pen pal letters between a lonely woman-child and an elf from the North Pole without making anybody with halfway-developed critical faculties find you and take some sort of revenge. Well, that’s not the strongest story here, but she pulled off okay the elf thing and I have no clue how (what sounds feasible about “pulling off the elf thing”?). Dalton uses the shorter short fiction form to her advantage. There was no story (most are about five pages in the largest font you can sort of get away with) I wanted to be longer. She knows how long something can go on for; depth accumulates, but each story is a few weirdly shallow gasps. The episode I found most arresting was part of an essayish triptych anecdotally describing how things, blood namely, can come to drool across floor tile. This particular section of the barely six-page piece is less than two pages; it depicts in careful/squirmy portraiture the event of a boy taking a shower in a scummy apartment and a “mutant salamander” emerging from the drain. The result is not hygienic or pleasant, but demonstrating an economy of discomfort and Lilliputian trauma.

The story of an attempt at throwing a house party begins ruined by a guest, missing a shoe, breathlessly approaching the host: “‘Your fucking friend just attacked me,’ she says. She was in my basement music room so no one heard her yelling through the egg-crate covered walls. I’m hosting a Hawaiian-themed party.” The creep who stole the girl’s shoe after harassing her is a total failure who can’t quite fit well enough into the way things go and who suffers from crippling social problems. The narrator, who herself has positive intentions (a nice luau, like what? the details of the music room being pretty heartbreaking, too), tries to understand the creep: “He didn’t seem dangerous, just fetishistic.” Another story begins similarly with the narrator and her boyfriend Matt having a “luxury” pork meal to celebrate his latest painting. The painting is “as long as a Honda, and as tall as our ceiling. Red-barked trees, squirrels, and naked women cover the canvas.” The constant miracle of this book is that it never slouches into lazy Napoleon Dynamite twee/preciousness; despite how close it comes it then swoops back into the realm of literary skill as assuredly as a stunt pilot pulling out of a nosedive right before hitting the water. The turn in this flash-length storylet is when Matt can’t stop himself from doing the “wrong” thing (he eats all the copious pork leftovers cold for breakfast: “I just ate a huge pile of lard, basically”), getting miserably ill as consequence, and the narrator can’t help but desiring him more for his disabled judgment. Elsewhere: the narrator imagining she is Snow White --- with glass coffin, singing chipmunks, and all --- during a sexual encounter in her backyard garden. The scene is tenderly pathetic and, ultimately, emotionally affirmative (hell, wide eyed). “Everything went white as I came, as if the moon suddenly got brighter.” Most of the characters in these stories act like high functioning autistics. When the simplest aspects of getting by in life are rendered as impossibly fraught, the result is highly unnerving as safety divorces from routine. The balance between childish awe and psycho nervousness is the best hit of Wide Eyed. There is no reason this book works more than that Trinie Dalton has a major handle on her craft and knows how to channel her bizarre fixations (is that me projecting?) into the kind of art that you appreciate as it makes you feel uneasy about the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment